AVs would need to be substantially safer than human drivers to gain public acceptance.

UK Government accepts the Law Commission’s recommendations on AVs

On 19/08/22 the government published its policy paper, ‘Connected and automated mobility 2025: realising the benefits of self-driving vehicles’, along with a number of other papers and research studies including ‘International perceptions of the UK’s connected and automated mobility sector’ and ‘Responsible Innovation in Self-Driving Vehicles’.

The government paper serves as a response to the Law Commission’s recommendations for automated vehicles which we commented on here) and includes a new consultation on creating a new legal and safety framework, with responses due by 14/10/22.

The government congratulates the Law Commission and welcomes their recommendations which it says it will use to develop legislation within the forthcoming Transport Bill.

The government sets out some headline grabbing stats including that by 2035, 40% of new cars in the UK may have self-driving capabilities and that the industry could create 38,000 jobs and £42billion in revenue. But from the point of view of insurers, perhaps the more interesting development is that the government proposes a level of safety for automated vehicles in line with that expected of a human driver, i.e., competent and careful. This can be contrasted with comments made by the Law Commission that “everyone agreed that AVs should be safer than human drivers in general” and that some considered “AVs would need to be substantially safer than human drivers to gain public acceptance”.

Elsewhere, the report contains some interesting commentary on the Law Commission’s recommendations in Annex D, including as follows:

- A new Automated Vehicles Act to regulate automated vehicles will be implemented in the Transport Bill.

- There will be broad duties on ASDEs (Authorised Self-Driving Entities) to, for example, ensure vehicles are safe throughout their life, to ensure cybersecurity and to share data with regulators.

- An in-use regulatory scheme must be established to ensure automated vehicles remain safe throughout their lives.

- It’s likely ASDEs will have a duty to ensure users of automated vehicles understand how they operate.

- The government will seek to sanction ASDEs where there is a lack of due diligence but also wants to move towards a no blame safety culture, much like the aviation sector.

- There will be new offences relating to misleading marketing, i.e., marketing a vehicle as including an automated driving feature where it has not been so authorised.

- The government supports the concepts of the user-in-charge and the No User-in-Charge (NUiC) Operator.

- The listing of automated vehicles under Section 1 of the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018 will be replaced with authorisation records.

- The government agrees that reviewing product liability law is “a very important issue and we will be engaging more widely with government to understand next steps”.

- There will be a consultation on a new data regime on the collection, retention and sharing of data relevant for insurance purposes.

Imminent arrival of ALKS?

The Department for Transport continues to revise its prediction for when Automated Lane Keeping Systems (ALKS) will be available in UK cars with its most recent guess being that the technology will be ready (and approved) by the end of 2022. (2023 is perhaps more likely.)

Elsewhere, Mercedes-Benz has launched its version of ALKS, which it calls ‘Drive Pilot’, in Germany. The system is the first to achieve Level 3, where the vehicle can drive itself under limited conditions, i.e., when in traffic, at speeds of up to 37mph.

Changes to the Highway Code

As has been well publicised, changes were made to the Highway Code on 01/07/22 to address the safe use of AVs (none yet having been listed here; but, as above, it may only be a matter of time). The changes clarify that whilst a vehicle is driving itself (within the meaning of the AEV Act 2018) the user does not need to monitor it and can in fact do something else, like watch content on an in-built screen. But he or she cannot use a handheld mobile phone.

In its report on automated vehicles, the Law Commission recommended that users of AVS should be allowed to engage in some limited activities when the vehicle is driving itself – so long as they are able to take back control in response to a ‘transmission demand’. The report recommended a cautious approach regarding the use of phones but considered the use of in-built screens as less intrusive because the screen will cut out at the start of a transition demand.

For motor insurers, the transition demand and the ability of the user to respond to it will be important considerations when considering the risks associated with AVs, particularly given that a failure to respond to a transmission demand can mean the user becomes culpable for any resulting collision.

Remote driving

On 24/06/22 the Law Commission (LC) published an issues paper seeking views on the regulation of remote driving on UK roads. In particular, the LC asks whether the current law causes any problems in practice and considers the options for reform. Responses are due by 02/09/22.

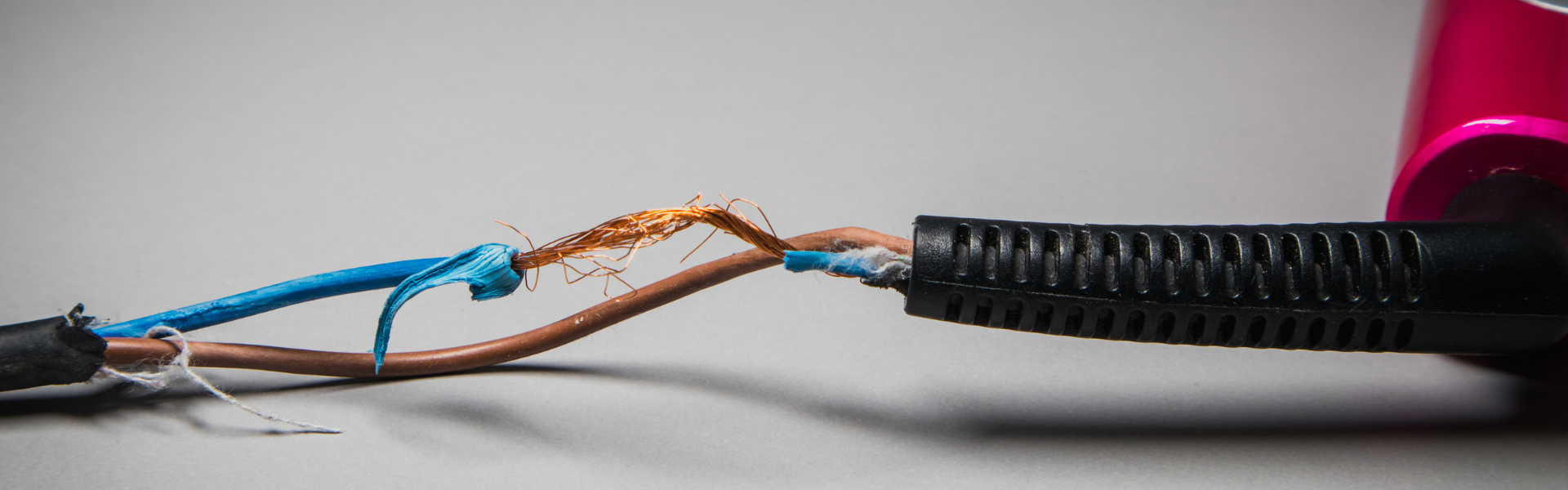

Remote driving, according to the paper, is where a person is outside the vehicle and uses wireless connectivity to performs some or all the driving task or to at least monitor the driving environment with a view to responding if needed.

Some may wonder what purpose remote driving would serve, particularly whilst the industry works towards automated vehicles. Of course, remotely controlled vehicles have long been used in hazardous environments like mines. (There’s a few on Mars right now.) But that would normally be on land not subject to road traffic regulation. There are also vehicles offering remote parking assist and summon features but that may not satisfy the definition of remote driving because the user is not necessarily performing the driving task (but is prompting the vehicle to drive itself). One other example given in the paper is the delivery of rental cars which could save on manpower if performed remotely. Perhaps a more realistic scenario is the use of remote driving as an adjunct to automated driving, perhaps being deployed in the event an automated vehicle (with no user inside) gets itself into trouble.

Chapter 4 of the paper deals with civil liability and raises some pertinent questions as to who would be liable in the event of an accident involving a remotely driven vehicle. If such an accident were caused by the remote driver, then the position may be relatively straightforward; but what if the accident were caused by a failure of connectivity or by the software being used to control the vehicle or the vehicle itself? Those involved in the Law Commission’s consultation on automated driving may feel a sense of déjà vu when grappling with these issues.

The report also quite rightly picks up on the safety challenges facing remote driving, the key ones being connectivity (i.e., latency and service interruptions) and the poor situational awareness of a remote driver.

Transport Committee inquiry on automated vehicles

Following the announcement of the Transport Bill, the Transport Committee announced an inquiry scrutinising the development and deployment of automated vehicles on 27/06/22. It issued a call for evidence with a deadline of 22/08/22.

Among other things, the Transport Committee says it is interested in the likely uses of AVs, the progress of trials, the implications for infrastructure, safety and the effects on car ownership.

You may also like

The rise of automated driving features and the impact on motor claims

After a flurry of activity in 2022, the march towards fully automated self-driving seems to have stalled somewhat in 2023....

Product Liability Bitesize – December Edition

When we first started producing these quarterly updates covering all things product liability (check our earlier editions), we wondered whether...

Product Liability Post-Brexit Update

We’re now nearly two years from when the transition period under the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement came to an end, but...

Product Liability Bitesize – September Edition

It’s been a busy time since the first edition of our regular product liability update. The Queen’s Speech heralded new laws...